Gothic art isn’t a single style, it’s a recurring mood that resurfaces in every era. From cathedrals to surrealism to digital dreamscapes, certain images echo the same strange mixture of beauty, dread, and revelation. What follows is a very brief tour through that evolving shadow, a journey from medieval light to modern melancholy.

🕯️ Love exploring the eerie? Join the Eerie Dispatches newsletter for new stories, dark travel inspiration, and behind-the-scenes adventures.

1. Gothic Beginnings: Cathedrals & Sacred Light (12th–15th Century)

Gothic art began not on canvas but in towering stone cathedrals, built to inspire awe, fear, devotion, and wonder. Their soaring arches, stained-glass windows, and illuminated panels became vessels of spiritual storytelling. Light itself was treated as a sacred medium, revealing jewel-bright color by day and deep, contemplative shadow by night.

Artists & Works

Unknown Master of the Wilton Diptych

The Wilton Diptych (c. 1395) — This jewel-toned devotional panel, painted in ultramarine and gold leaf, presents King Richard II kneeling before the Virgin and Child amid a host of blue-robed angels. The luminous surfaces and delicate detailing create a sense of sacred stillness, as though the scene exists outside the passage of time. Crafted with exquisite precision and courtly symbolism, the diptych invites contemplation in a hushed, radiant space where earthly devotion meets heavenly presence.

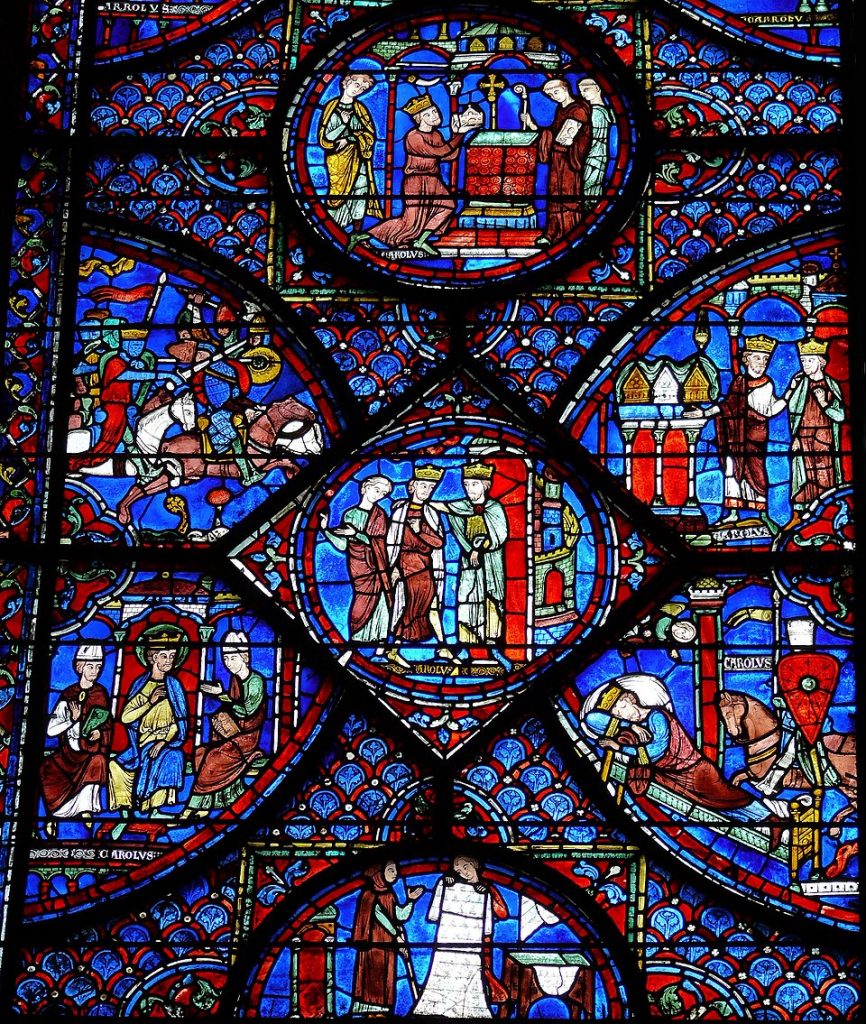

Chartres Cathedral

Stained Glass (c. 1200s) — The stained-glass windows of Chartres Cathedral still blaze above the town of Chartres, France, forming one of the most complete surviving ensembles of medieval glass in the world. Crafted by anonymous guilds of master masons and glassmakers, these panels glow with the famed “Chartres blue” and deep ruby reds, illuminating hundreds of scenes from scripture and medieval life. When sunlight pours through them, the cathedral becomes a radiant tapestry of sacred color, turning stone and shadow into living narrative.

Where to experience it:

To see the works:

The Wilton Diptych is housed in the National Gallery, London, where its ultramarine glow and gold-leaf radiance can be viewed up close.

The stained-glass windows of Chartres Cathedral remain in their original setting in Chartres, France, and the cathedral is open to the public for daily visits.

To feel the era:

Visit any space washed in colored light. A cathedral or chapel with stained glass will echo the reverent glow and spiritual hush that define medieval Gothic art.

Or spend time in a museum’s medieval galleries, where illuminated manuscripts, icons, and gilded altarpieces recreate the contemplative stillness at the heart of early Gothic devotion.

2. The Romantic Revival: Ruin, Storm & the Sublime (18th–19th Century)

Romanticism reclaimed Gothic emotion by looking outward, to abandoned abbeys, storm-laden skies, and landscapes vast enough to dwarf human certainty. This era embraced the sublime: beauty edged with dread, nature at its most dramatic, and ruin as a form of revelation.

Artists & Works

Caspar David Friedrich

The Abbey in the Oakwood (1809–10) — In this somber landscape, a small procession of monks carries a coffin toward the ruins of a Gothic abbey, its arches broken and silhouetted against a winter sky. Bare oak trees rise like skeletal witnesses, emphasizing the tension between spiritual ritual and the vast indifference of nature. Painted with Friedrich’s signature stillness and melancholy, the scene becomes a meditation on mortality, faith, and the haunting beauty of abandonment.

John Martin

The Great Day of His Wrath (1851–53) — Martin unleashes a sweeping, apocalyptic vision: a fractured earth tilts toward a fiery abyss as cities crumble and mountains break apart. Figures are cast into darkness while molten light floods the horizon, creating a sense of cosmic judgment on an unimaginable scale. Painted with theatrical grandeur and meticulous detail, the work embodies Victorian fascination with catastrophe, prophecy, and the sublime power of destruction.

Where to experience it:

To see the works:

Caspar David Friedrich’s The Abbey in the Oakwood is housed in the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin, where its somber winter light and ruined arches can be seen in person.

John Martin’s The Great Day of His Wrath is part of the Tate Britain collection in London, on view in rotation with his other apocalyptic canvases.

To feel the era:

Seek out a place where nature feels immense, such as a windswept coastline, a storm rolling over hills, or the quiet remains of an old ruin can summon the dramatic awe at the heart of Romanticism.

Or wander a landscape at dusk or early morning, when vast skies, long shadows, and fleeting light evoke the sublime tension between beauty and dread that defined the Romantic Gothic imagination.

3. Pre-Raphaelite Gothic: Beauty, Death & Symbolic Longing (Mid–19th Century)

The Pre-Raphaelites brought Gothic sensibility into intimate, emotional realms. Here the Gothic is romantic rather than apocalyptic: lush foliage, doomed love, symbolic tokens, and a deep fascination with beauty suspended on the edge of sorrow.

Artists & Works

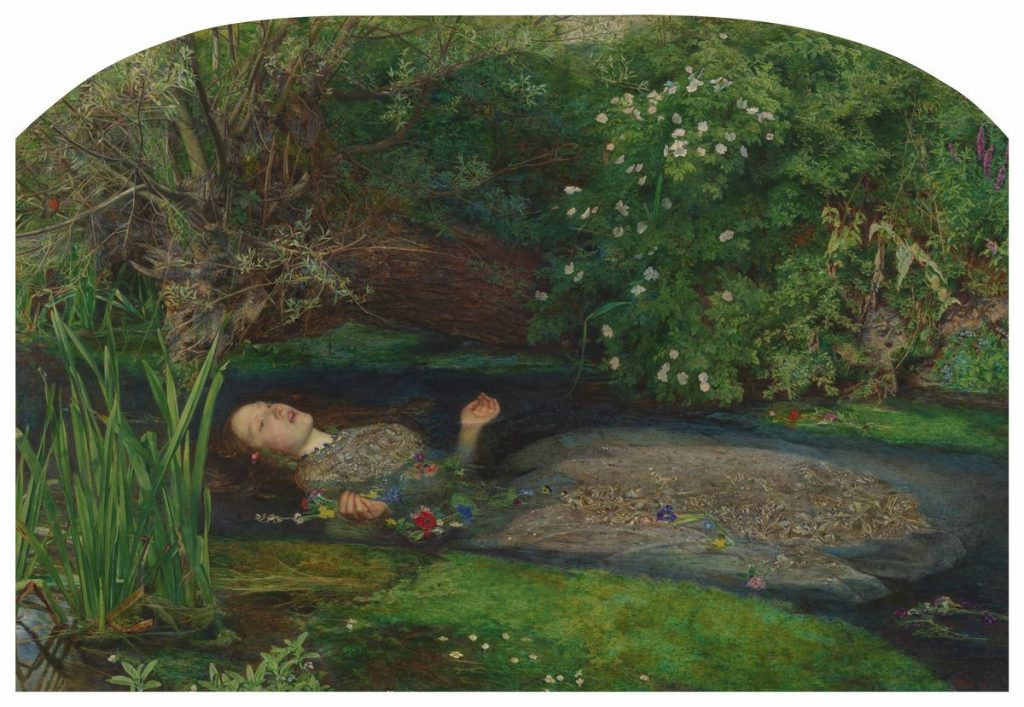

John Everett Millais

Ophelia (1851–52) — Millais portrays Shakespeare’s Ophelia in the final moments before her death, drifting along a river thick with wildflowers that echo the play’s symbols of innocence, grief, and unraveling. Her upturned hands and parted lips suggest a trance-like surrender as the water rises around her, her serenity at odds with the tragedy unfolding beneath the surface. Painted with meticulous botanical detail and luminous color, the scene becomes a haunting meditation on beauty suspended on the brink of loss.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Beata Beatrix (1864–70) — Rossetti transforms the death of Dante’s Beatrice into a vision of spiritual rapture, portraying her seated in a trance-like state as a red dove delivers a poppy, the symbol of her passing. Bathed in golden light that blurs the boundary between the earthly and the divine, her face lifts gently toward an unseen radiance, suspended in a moment between ecstasy and departure. Painted after the death of Rossetti’s own wife, Elizabeth Siddal, the work carries an intimate, devotional intensity that merges personal grief with poetic transcendence.

Where to experience it:

To see the works:

John Everett Millais’ Ophelia is housed at Tate Britain in London, displayed alongside other Pre-Raphaelite masterpieces that highlight the movement’s botanical detail and emotional intensity.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Beata Beatrix is also held in Tate Britain’s permanent collection, where its golden light and symbolic imagery can be viewed within the context of Rossetti’s broader artistic circle.

To feel the era:

Spend time in a lush garden or riverside setting, where overgrown foliage, drifting water, and soft natural light evoke the romantic melancholy central to Pre-Raphaelite vision.

Or explore a Victorian-era gallery filled with portraiture, poetry, and decorative arts, where themes of devotion, longing, and symbolic beauty echo the emotional depth of this movement.

4. Modern Gothic: Surrealism, Occult Vision & the Quiet Uncanny (1900–1970)

Modern Gothic stepped away from landscapes and cathedrals and moved into the dream state, a realm of symbols, mysterious women, strange creatures, and psychological shadows. The uncanny became intimate rather than monumental, shaped by surrealism, myth, and the deeper currents of the twentieth century.

Artists & Works

Leonora Carrington

The Giantess (The Guardian of the Egg) (1947) — Carrington presents a towering, serene figure whose pale, mask-like face and opulent red gown evoke both innocence and occult power. Cradling a luminous egg—the symbol of creation and potential—she stands amid a ring of birds and mythic creatures that orbit her like guardians or omens. Painted with Carrington’s signature blend of surrealism, magic, and inner cosmology, the work becomes a meditation on feminine mystery, transformation, and the quiet authority of the otherworldly.

Edward Gorey

The Gashlycrumb Tinies (1963) — Gorey’s infamous alphabet of ill-fated children pairs Victorian sensibility with razor-dry humor, each panel rendered in his unmistakable cross-hatched ink line. As twenty-six tiny protagonists meet their absurd and macabre ends, the book transforms morbid playfulness into a study of style: elegant Gothic draftsmanship, theatrical staging, and a wit as crisp as the black-and-white world he creates. A modern classic of dark illustration, it captures the charm and chill of Gorey’s singular imagination.

Where to experience it:

To see the works:

Leonora Carrington’s The Giantess (The Guardian of the Egg) is part of private and museum collections, with significant holdings of her work at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin, where her surreal, occult-infused paintings appear in rotating exhibitions.

Edward Gorey’s The Gashlycrumb Tinies can be found widely in bookstores, and original drawings from the book can be explored at the Edward Gorey House in Yarmouth Port, Massachusetts, a museum dedicated to his life, art, and distinctive Gothic sensibility.

To feel the era:

Visit a museum gallery devoted to Surrealism or magical realism, where dreamlike figures, strange creatures, and symbolic landscapes echo the uncanny interior world of modern Gothic art.

Or seek out a quiet woodland, old library, or shadowed architectural space where stillness, imagination, and mystery intertwine, the kind of intimate, uncanny atmosphere that defined the era’s shift from outer ruin to inner dream.

5. Contemporary Gothic: Identity, Myth & Emotional Haunting (1970–Present)

Contemporary Gothic merges self, myth, and the surreal. It blurs boundaries between beauty and horror, innocence and menace, dream and shadow. This era explores the uncanny at a personal scale: the haunted body, the symbolic ritual, the psychological echo.

Artists & Works

Natalie Shau

Lilith (2010s) — Shau reimagines the mythic first woman as a porcelain-skinned figure suspended between beauty and menace, her gaze cool beneath baroque shadows and digital ornament. Soft light glints across her sculpted features, heightening the tension between innocence and the occult power she embodies. Blending surreal portraiture with dark glamour, the work becomes a contemporary icon of feminine mystique, temptation, and supernatural allure.

Mark Ryden

The Ecstasy of Cecelia (2008) — Ryden blends pop-surrealism with Victorian devotion, portraying Cecelia as a wide-eyed, porcelain figure bathed in soft, glowing light. Surrounding symbols, cherubic faces, delicate flowers, and ornate religious motifs, hover between innocence and uncanny mysticism. With its pastel palette and quietly disquieting sweetness, the painting becomes a modern Gothic icon, exploring the borderlands where childhood imagery meets spiritual wonder and subtle unease.

Where to experience it:

To see the works:

Natalie Shau’s Lilith is part of her digital portfolio and appears regularly in exhibitions at contemporary pop-surrealist galleries such as Corey Helford Gallery in Los Angeles, where her digitally rendered, baroque-dark portraits are shown alongside other visionary artists.

Mark Ryden’s The Ecstasy of Cecelia is held in private and rotating gallery collections, with significant displays of his work at venues like the Frye Art Museum in Seattle and Corey Helford Gallery, key hubs for modern pop-surrealism.

To feel the era:

Explore a contemporary art space that highlights pop surrealism, digital art, or new-mythic portraiture, where themes of identity, ritual, and emotional haunting reflect the Gothic’s evolution into the 21st century.

Or experience immersive environments like candlelit installations, baroque-styled galleries, or theatrical, dreamlike exhibitions, where beauty, symbolism, and modern melancholy meet in the same charged atmosphere that defines contemporary Gothic mood.

Closing

From illuminated altarpieces to today’s dramatic, digitally-created fantasy art, Gothic art has always balanced beauty and shadow, devotion and doubt, ruin and imagination. Across centuries, it has explored one idea again and again: the thin border between the beautiful and the unsettling.

📖 If you enjoyed this story, you’ll love Eerie Escapes — the book that inspired it all. Learn more here.