Every year, more cold cases are being solved, from missing persons and unidentified bodies to decades-old mysteries that once seemed impossible to untangle. And the breakthroughs aren’t always happening inside police departments. In fact, some of the most astonishing case solves of the past decade have come from unexpected places, including satellite imagery, genetic genealogy, and even YouTube dive teams.

Take William Moldt, for example. He vanished in 1997 after leaving a Florida nightclub, and for over 20 years, no one knew what had happened. Then in 2019, a former resident, viewing the area where he once lived on Google Earth, noticed something unusual in a nearby retention pond. A drone later confirmed the discovery: a sunken car. Inside the vehicle, submerged in a retention pond, behind a quiet neighborhood, were Moldt’s remains.

In Philadelphia, a mystery that had gripped the city since 1957 was finally answered in 2022. The “Boy in the Box,” an unidentified child found beaten and abandoned in a cardboard box, was identified through genetic genealogy as Joseph Augustus Zarelli. It was a breakthrough 65 years in the making, thanks to emerging forensic tools and dedicated cold case teams.

And in rural Tennessee, Erin Foster and Jeremy Bechtel, two teens who vanished in 2000, were finally located more than 20 years later when a civilian dive team using sonar technology discovered their submerged vehicle in the Calfkiller River. The car had gone undetected in earlier searches, but a renewed examination of the area with modern underwater imaging revealed what had long been missed. For their families, the answer wasn’t the one anyone wanted, but it finally replaced years of uncertainty with long-awaited answers.

These cases highlight something extraordinary. Mysteries that once lingered for decades are now being unraveled by tools, technologies, and collaborations that simply did not exist before. Crowdsourced sleuthing, forensic breakthroughs, and creative uses of data are transforming what “unsolvable” really means.

But this transformation is not limited to the past. Modern cases are also being solved faster and at higher rates than ever before. From real-time phone data and widespread surveillance to rapid DNA analysis and digital records that track movement and behavior, today’s investigations often begin with a depth of evidence that detectives in earlier generations could never have imagined. In the 2018 murder of Mollie Tibbetts, investigators reviewed thousands of hours of footage from homes and businesses across multiple towns, ultimately identifying a vehicle pattern that led directly to her killer within weeks. Crimes that might once have taken years to piece together, or never been solved at all, are now increasingly resolved within days, weeks, or months. In many ways, cold cases simply make the change more visible. The same forces are reshaping how all crimes are investigated from the moment they occur.

Below, we’ll explore the 12 biggest reasons more cases, both old and new, are being solved now than at any other time in history. While many of these tools have roots stretching back decades, the past twenty years feel like a turning point from earlier investigative eras, with the last decade in particular showing an unprecedented acceleration in how quickly and reliably cases are solved.

🕯️ Love exploring the eerie? Join the Eerie Dispatches newsletter for new stories, dark travel inspiration, and behind-the-scenes adventures.

DNA

1. Advances in DNA Testing Technology

Modern DNA science has greatly increased what evidence can be tested and how reliably it can be analyzed. Over the past decade in particular, forensic labs have made major gains in extracting usable DNA from far smaller, more degraded samples than ever before, including trace touch DNA, aged biological material, and evidence once considered unusable. Improvements in extraction methods, amplification sensitivity, contamination control, and re-testing techniques mean that evidence collected decades ago can now yield results that were impossible at the time. In many cases, long-stored rape kits, clothing, or crime scene items are being reexamined with entirely new outcomes, turning once-dormant evidence into powerful investigative leads.

Example case: Kristin Smart

Kristin Smart disappeared in 1996 after attending a college party in California, but for decades the case stalled due to a lack of usable forensic evidence. While suspicion focused early on a fellow student, investigators were unable to produce conclusive results using the DNA testing methods available at the time. In the late 2010s, advances in DNA extraction and testing sensitivity allowed forensic analysts to reexamine physical evidence that had previously yielded no meaningful results. Modern techniques made it possible to detect and interpret trace biological material from decades-old evidence, helping transform long-inconclusive findings into actionable forensic proof. This renewed DNA analysis played a critical role in finally securing an arrest and conviction more than 25 years after Smart’s disappearance.

How you can help:

Organizations like End the Backlog work to eliminate untested rape kits and ensure modern DNA testing is applied to long-neglected evidence. Their Take Action page outlines simple, meaningful ways to get involved, from advocacy efforts to policy support, helping turn stored evidence into answers.

2. Genetic Genealogy

Genetic genealogy takes DNA analysis a step further by expanding where investigators can look for matches. Before this approach, crime scene DNA could only be compared to law enforcement databases such as the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS), which primarily contains DNA collected from people who have been arrested or convicted of certain crimes and are legally required to submit a sample. If a suspect had never been arrested or entered into the system, DNA testing often led nowhere. Genetic genealogy changes that limitation by allowing crime scene DNA to be compared to family members in public genealogy databases, even when the suspect themselves has never submitted DNA. Using platforms like GEDmatch, investigators and genetic genealogists build family trees from partial matches, gradually narrowing the pool of possible individuals. Rather than waiting for a direct match, this technique allows investigators to work backward through shared ancestry, turning family connections into powerful investigative pathways that have reshaped how cold cases are solved.

Example case: Joseph James DeAngelo (Golden State Killer)

Often cited as the landmark case that brought genetic genealogy into public awareness, the Golden State Killer investigation spanned more than four decades. Between the mid-1970s and mid-1980s, the offender committed a series of burglaries, sexual assaults, and murders across multiple California jurisdictions, leaving behind DNA evidence that investigators were able to preserve and profile years later. Despite having usable DNA, traditional law enforcement databases repeatedly failed to identify a suspect because DeAngelo had never been arrested for a qualifying offense and therefore had no profile in CODIS. In 2018, investigators uploaded crime-scene DNA to GEDmatch, where distant familial matches allowed genealogists to build family trees and gradually narrow the pool of possible suspects. This approach ultimately led investigators to DeAngelo, resulting in his arrest more than 40 years after his crimes began and fundamentally changing how cold cases could be solved.

– Genetic Genealogy Highlight: Identification of Does: Giving Names Back to the Unknown

One of the most profound outcomes of genetic genealogy has been the identification of unknown victims, often referred to as “Does.” Through forensic genealogy, investigators can now match DNA from unidentified remains to distant relatives in public databases, allowing names to be restored to people who were once reduced to case numbers. Platforms like NamUs and organizations such as the DNA Doe Project play a central role in this work, combining science, archival research, and volunteer effort to reconnect families with long-lost loved ones. These identifications may not always lead directly to a suspect, but they close decades-long chapters of uncertainty, restore dignity to the dead, and often reopen investigations with new context and renewed urgency.

How you can help:

Genetic genealogy depends on people choosing to make their DNA available for investigative comparisons. While many consumer DNA testing companies, such as Ancestry.com, do not allow law enforcement access to their databases, individuals can take an additional step by exporting their DNA data and uploading it to platforms like GEDmatch, which allows users to opt in to law-enforcement matching for violent crime and unidentified remains cases. Without this extra step, DNA profiles tested through consumer sites remain inaccessible for investigative use. Getting your DNA tested and choosing to upload and opt in can help identify unknown victims, solve violent crimes, and bring long-awaited answers to families, while still allowing individuals to control their privacy settings.

Digital & Environmental Evidence

3. Surveillance Footage & Environmental Cameras

The widespread presence of environmental surveillance has begun to reshape criminal investigations by changing what happens in the earliest hours of a case. Doorbell cameras, business security systems, traffic cameras, license plate readers, dashcams, and public CCTV now create vast networks of passive observation that didn’t exist even a decade or two ago. This footage often captures people, vehicles, and timelines unintentionally, preserving movements that might otherwise rely on fading memory or incomplete witness accounts. While surveillance rarely aids long-cold cases due to limited retention periods, it plays a powerful role in preventing cases from going cold at all, allowing investigators to establish timelines, identify vehicles, and narrow suspects quickly. Evidence that once would have vanished now shapes investigations from the outset, making modern cases faster, more precise, and far less dependent on chance.

Example Case: Bryan Kohberger

The 2022 murders of four University of Idaho students were solved partly through the rapid use of environmental surveillance and digital video evidence. In the days following the killings, investigators gathered and analyzed footage from residential cameras, business security systems, and traffic cameras across multiple towns and highways. This video evidence helped establish a timeline, identify a suspect vehicle, and track its movements before and after the crime. By locating and preserving footage quickly, investigators were able to narrow their focus early, corroborate digital data, and prevent the case from stalling. In this case, the some of the most important evidence wasn’t eyewitness testimony or a confession, but a trail of cameras from porches, parking lots, and traffic feeds, with each one capturing something incomplete, but together narrowing the field of possibilities.

How you can help:

Environmental surveillance is only useful if footage can be located and preserved quickly. Many communities now offer voluntary camera registry programs that allow residents and businesses to register security cameras in advance, making it easier for investigators to identify potential sources of footage in the critical early hours of a case. Participating in or advocating for local camera registries helps ensure valuable video evidence is found before it is automatically deleted, reducing the chances that a case goes cold due to lost information.

4. Phone Data, GPS & Digital Movement Records

Mobile phones generate detailed digital footprints that have become invaluable to modern investigations. Call logs, text metadata, GPS location data, app usage, internet search history, and time-stamped activity can reconstruct a person’s movements, behavior, and even intent with striking precision. Unlike environmental surveillance, this data is self-generated, coming directly from a suspect’s own device, often revealing patterns that undermine alibis or expose previously unknown connections. In some cases, search queries themselves provide insight into planning or deception, capturing questions a suspect asked long before investigators ever did. Even in older cases, retained phone records and recovered digital data can now be reanalyzed using modern tools, allowing investigators to trace routes, confirm proximity, and establish timelines that were once based largely on memory and assumption.

Example case: Alex Murdaugh

In the 2021 murders of Maggie and Paul Murdaugh, digital evidence from Alex Murdaugh’s own devices played a decisive role in dismantling his alibi. Phone location data, step counts, and time-stamped activity showed Murdaugh moving rapidly around the family property at the precise window when the murders occurred, despite his claims that he was elsewhere and asleep. Additional data placed him at the crime scene minutes before the killings and tracked his movements immediately afterward, creating a detailed timeline that conflicted sharply with his statements to investigators. What ultimately unraveled Murdaugh’s alibi wasn’t a single dramatic revelation, but the quiet accumulation of digital time stamps, details he never realized were building a record of his night.

How you can help:

Access to phone data often depends on how quickly an investigation escalates and whether critical information can be preserved. Taking steps to enable emergency features on your own devices, such as location sharing, emergency contacts, and medical or emergency access settings, can help responders act faster if something goes wrong. Encouraging loved ones to do the same, and understanding how digital data is preserved in the earliest hours of a disappearance, can make a meaningful difference when time matters most.

Human & Public Amplifiers

5. Growing Awareness of Biases & Wrongful Convictions

Public understanding of investigative bias and wrongful convictions has grown significantly over the past few decades, reshaping how cold cases are reviewed and challenged. High-profile exonerations, advances in forensic review, and the work of innocence organizations have exposed how tunnel vision, coerced confessions, unreliable witnesses, and flawed forensic practices once led to devastating errors. This growing awareness has made both the public and law enforcement more willing to reexamine old cases with fresh eyes, question long-held assumptions, and correct past injustices. In many instances, cases are reopened not because of new evidence alone, but because investigators are now more prepared to confront the possibility that the original investigation got it wrong and to treat doubt itself as a legitimate investigative tool.

Example case: Anthony Ray Hinton

Anthony Ray Hinton was wrongfully convicted of two murders in Alabama based almost entirely on flawed forensic testimony and spent nearly 30 years on death row before being exonerated in 2015. His conviction relied on an unqualified firearms expert whose conclusions were later unanimously rejected by independent specialists, leaving no physical evidence tying Hinton to the crimes. Hinton’s case became a modern example of how confirmation bias and unreliable forensic practices can sustain wrongful convictions for decades, and how increased willingness to confront those failures has led to meaningful reexamination and correction in the current era.

How you can help:

Organizations like the Innocence Project work to review questionable convictions, provide legal and forensic expertise in post-conviction cases, and advocate for systemic reforms that reduce the risk of future wrongful convictions. Their work includes challenging unreliable forensic practices, addressing eyewitness misidentification, and pushing for safeguards that make investigations and trials more accurate. Supporting these efforts through donations, education, or advocacy helps correct past mistakes while strengthening the integrity of the justice system going forward.

6. Social Media & Storytelling

Digital storytelling has transformed how both cold cases and active investigations are remembered, discussed, and revisited. Podcasts, YouTube documentaries, short-form video explainers on TikTok, and online communities have brought forgotten cases back into public consciousness while also maintaining sustained attention on new ones as they unfold. By breaking down complex timelines, amplifying victim stories, and encouraging responsible public engagement, creators help turn passive audiences into attentive witnesses. This renewed attention can generate new tips, preserve critical details, and occasionally place key information in front of someone who recognizes a name, a place, or a moment. In an era where attention itself can drive progress, responsible storytelling has become a powerful catalyst for renewed investigation.

Example case: Jason Callahan (“Grateful Doe”)

A young man who died in a 1995 car accident remained unidentified for two decades and became known as “Grateful Doe” because of Grateful Dead memorabilia found with him. His case was well known within the Doe and web sleuth communities for years, but no identification was possible because he had never been reported missing. In 2015, Jason Callahan was reported missing, nearly 20 years after his disappearance, leaving investigators with limited information and no clear leads. People close to his family began sharing Jason’s missing person flyer on social media, where it spread beyond his immediate circle and reached members of the Doe community familiar with Grateful Doe. That connection led to the comparison of the two cases, and DNA testing later confirmed that Jason Callahan and Grateful Doe were the same person. The case shows how social media can bridge critical gaps by placing the right information in front of the right people at the right time, even decades later.

How you can help:

Public attention can be powerful, but it also carries responsibility. In recent years, some individuals have used social media to harass victims’ families, accuse uninvolved people, or spread unverified claims, causing real harm to those already living through trauma. Ethical engagement means sharing accurate information, avoiding speculation, and respecting the privacy and dignity of victims, families, and witnesses. Choosing not to dox, harass, or publicly accuse others helps ensure that storytelling supports justice rather than undermines it.

7. Private Dive Teams & Sonar Technology

Civilian dive teams equipped with sonar, underwater drones, and advanced imaging have solved a growing number of long-missing person cases by locating submerged vehicles that were overlooked for decades. While sonar technology itself has existed for years, falling costs and improved usability have made it accessible to trained civilians, helping drive the rise of volunteer dive teams able to deploy these tools consistently. These groups often reexamine old disappearances with fresh eyes, questioning assumptions about search areas and accident scenarios. Using sonar to scan rivers, lakes, and retention ponds, they can quickly identify vehicle-shaped anomalies that traditional searches missed. Groups like Chaos Divers have helped bring closure to families by recovering vehicles and remains, often revealing that disappearances once suspected as foul play were tragic accidents. In many cases, the breakthrough did not come from new technology alone, but from broader access, persistence, and a willingness to rethink old searches, proving that answers can remain hidden in plain sight for years.

Example case: Chaos Divers recover submerged car linked to Karen Schepers (Illinois)

In 2025, volunteer search and recovery team Chaos Divers located the submerged vehicle of Karen Schepers, a woman who vanished after a night out in Carpentersville, Illinois, in 1983. The dive team used sonar to scan the Fox River, eventually identifying a vehicle that matched her missing car’s description, decades after it slipped beneath the surface. The discovery came after renewed investigative interest and coordinated sonar searches, helped by Chaos Divers’ willingness to deploy modern scanning tools in water bodies overlooked by earlier searches. The frozen car’s location offered long-awaited answers for Schepers’ family and demonstrated how accessible sonar and persistent revisitation of old search areas can unearth crucial evidence that initially went undiscovered.

How you can help:

Volunteer dive teams rely on public support to continue long, resource-intensive searches that many families could not pursue on their own. Supporting reputable recovery organizations such as Chaos Divers, Dive Recovery Network, Trails to Hope, and Search Squad through donations, equipment funding, or awareness helps expand access to sonar searches and underwater imaging for long-missing persons cases. Just as importantly, sharing accurate case details and respecting search protocols ensures these efforts complement, rather than complicate, official investigations and give families the best chance at answers.

8. Public Databases & Crowdsourcing

Many cold cases are being moved forward not by institutions alone, but by ordinary people who choose to participate. Public-facing databases such as NamUs, The Doe Network, and The Charley Project rely on volunteers who carefully review case files, compare missing persons reports, analyze reconstructions, and submit potential matches through established channels. Online communities across forums and social platforms, including long-running true crime discussion boards, help keep cases visible and actively examined over time. Even genetic genealogy depends on public participation, with platforms like GEDmatch existing only because individuals voluntarily upload their DNA to help identify unknown victims and perpetrators. Together, these efforts reflect a collective, deeply human commitment to restoring names, stories, and dignity to those who might otherwise remain forgotten.

Example case: Michelle Garvey

Michelle Garvey disappeared from Connecticut in 1982, and her remains were discovered later that year in Texas, where she remained unidentified for more than three decades. In 2014, a member of the public reviewing NamUs and Doe Network case listings noticed striking similarities between Garvey’s missing person report and an unidentified Jane Doe profile. The potential match was submitted to authorities, prompting renewed investigation and DNA testing that confirmed her identity. The case demonstrates how structured public participation in open databases can generate decisive leads, with modern forensic testing providing the final confirmation.

How you can help:

If you want to contribute to this effort, you can review public case listings, carefully compare details, and submit potential matches through official channels when appropriate. Donating to the nonprofits and databases that host and maintain these records helps fund the infrastructure that makes this work possible.

9. Public Access to Records

Greater public access to historical records has dramatically expanded who can investigate cold cases and how deeply they can be examined. FOIA laws, digitized newspaper archives, online court records, and released police files now allow journalists, researchers, and independent investigators to study cases that were once accessible only to law enforcement. This expanded access has surfaced overlooked details, contradictory witness statements, and investigative missteps that may have gone unnoticed for decades. In many cases, breakthroughs come not from new evidence, but from revisiting old records with fresh perspective, critical distance, and a willingness to question long-standing conclusions.

Example case: Curtis Flowers

Curtis Flowers was tried six times for the same 1996 murders in Mississippi, with repeated convictions overturned due to prosecutorial misconduct. Over the years, journalists, researchers, and legal advocates examined publicly available court transcripts, police records, and trial filings, uncovering patterns of suppressed evidence, contradictory witness testimony, and racially biased jury selection. Expanded access to these records allowed independent scrutiny that ultimately led to Flowers’ release in 2019, showing how transparency and persistent review of historical documents can fundamentally alter the course of a case.

How you can help:

Access to records depends on laws, funding, and public pressure to keep government information open. Supporting organizations that defend transparency and public records access helps ensure journalists, researchers, and advocates can continue examining cases responsibly. You can also support local journalism, which often relies on public records to uncover overlooked details and hold institutions accountable long after a case has faded from headlines.

Dedicated Effort & Specialized Techniques

10. Cold Case Units & Grant Funding

The creation of dedicated cold case units has fundamentally changed how long-unsolved investigations are handled. Rather than being sidelined by active caseloads, these cases are now assigned to specialized teams with the time, training, and institutional support to pursue them properly. New grant funding at the state and federal level has further enabled departments to revisit evidence, apply modern forensic techniques, and collaborate with outside experts. This structural shift reflects a growing recognition that cold cases are not unsolvable. They are resource-intensive, and with sustained investment, many are finally receiving the focused attention they deserve.

Example case: Lonnie Franklin Jr. (The Grim Sleeper)

For decades, dozens of murders in Los Angeles were believed to be the work of the same killer, but the cases remained fragmented across time and jurisdictions. The creation of dedicated cold case teams and the allocation of sustained resources allowed investigators to systematically reexamine evidence, connect patterns across years, and prioritize long-neglected victims. In 2010, this focused effort led to the arrest of Lonnie Franklin Jr., bringing resolution to cases that had lingered for more than 25 years. The case demonstrates how specialized units and long-term investment can succeed where traditional investigative models fall short.

How you can help:

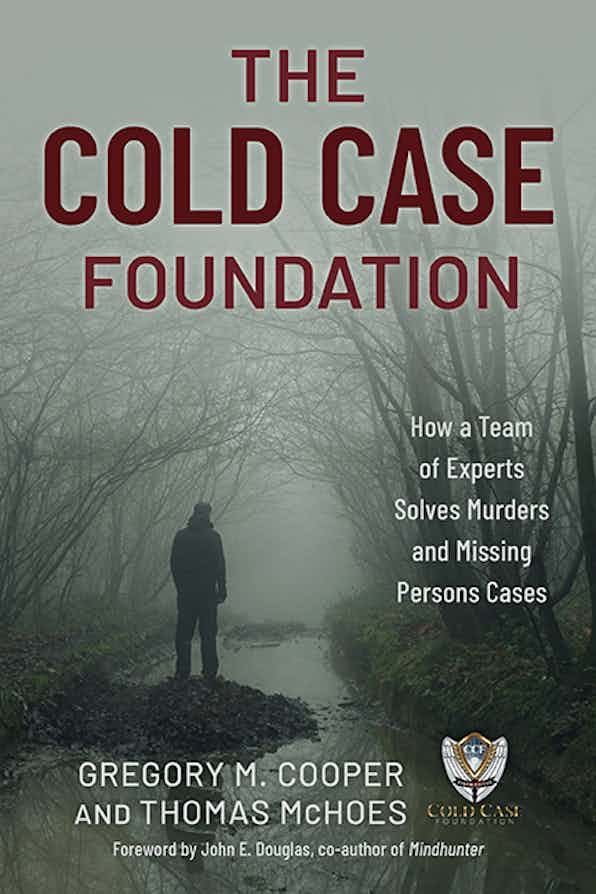

Dedicated cold case units are typically funded through public dollars and government grants. However, there is an independent, nonprofit organization called the Cold Case Foundation, that is also doing amazing work in this area. It is made up largely of experienced retired investigators and forensic experts who volunteer their time to work on long-unsolved cases. Supporting this organization helps extend the reach of publicly funded cold case units by providing additional expertise, training, and case review support that complements government investment in cold case investigations.

11. Improved Inter-Agency Collaboration

For much of the past century, criminal investigations were constrained by jurisdictional boundaries, with agencies often operating in isolation and sharing little information. In recent years, improved data systems and institutional mandates have made cross-agency collaboration far more common. Police departments now routinely share case files, forensic data, and arrest records across local, state, and federal databases, allowing investigators to identify patterns that would be invisible within a single jurisdiction. While this work often happens behind the scenes, it has become essential in connecting serial offenses, reopening cold cases, and preventing investigations from stalling due to fragmented information.

Example case: Ted Bundy (retrospective contrast)

Bundy’s crimes exposed the consequences of poor inter-agency communication, as similar offenses across multiple states were not connected in time to prevent further violence. In later decades, shared databases, standardized reporting, and cross-jurisdictional task forces allowed investigators to reexamine cases linked to him and to prevent similar failures in future investigations. Modern collaboration exists in large part because earlier cases like this demonstrated the cost of isolation.

12. Advanced Forensic Reconstruction

While genetic genealogy has transformed victim identification, advanced forensic reconstruction remains a critical supporting tool in many cold cases. Techniques such as isotope testing, 3D facial reconstruction, skeletal analysis, and modern imaging help investigators narrow geographic origins, estimate age and lifestyle, and build more accurate profiles of unidentified victims. In cases where DNA is degraded, unavailable, or yields multiple possible matches, these methods provide essential context that guides further investigation. Rather than replacing newer technologies, forensic reconstruction works alongside them, helping investigators focus their efforts and restore a clearer, more human story to unidentified remains.

Example case: Peggy Johnson (formerly “Racine County Jane Doe”)

Peggy Johnson was found murdered in Wisconsin in 1999 and remained unidentified for years. During a modern reexamination of the case, investigators used forensic reconstruction techniques, including isotope testing, to better understand her background and possible geographic history. This contextual forensic work, combined with later DNA analysis, ultimately led to her identification and the arrest of a suspect decades after her death. The case illustrates how reconstruction methods can provide crucial investigative direction when DNA alone is not immediately decisive.

How you can help:

You can support organizations that fund forensic reconstructions, laboratory work, and public case visibility for unidentified remains. Groups such as the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children help distribute reconstructions and age-progressed images, while the The Doe Network keeps unidentified persons cases searchable and accessible. Even sharing official reconstructions from trusted sources can place the right image in front of the right person.

AI on the Horizon

As investigative work becomes increasingly data-dense, artificial intelligence is poised to play a growing role in how cases are reviewed, organized, and advanced. Modern investigations generate enormous volumes of information, including reports, timelines, digital records, communications, video footage, and historical files that can span decades. AI systems are increasingly capable of synthesizing these materials, identifying patterns across disparate sources, flagging inconsistencies, and surfacing connections that may not be obvious when evidence is reviewed piece by piece. In the future, investigators are likely to use AI to rapidly reconstruct timelines, prioritize leads, reexamine cold cases with fresh analytical structure, and detect behavioral or geographic patterns across multiple cases. Rather than changing what investigators look for, these tools may fundamentally change how quickly and thoroughly they can look, allowing long-overlooked details to rise to the surface and giving stalled cases new momentum through clarity, organization, and scale.

Closing Thought

The era we’re living in is defined not by a single breakthrough, but by many small ones, better science, better records, better collaboration, and a growing willingness to revisit what was once dismissed as unsolvable. Cold cases remind us of what was missed. Modern cases show us what’s possible. Together, they point to a future where fewer crimes are left unsolved and fewer names are lost to time. If solving crimes continues to get faster and more reliable, we may well have a future to look forward to where fewer crimes are committed in the first place, since getting caught will become the almost definite outcome.

Curated Eerie Essentials

If you’d like to support the incredible work these nonprofits are doing, consider checking out some of their official merchandise. From apparel to accessories, each purchase helps fund their investigations, research, and outreach efforts—and wearing or using these items also spreads awareness about cold cases and missing persons. Below, you’ll find a few items I especially loved.

Innocence Project Logo Umbrella – Black umbrella with Innocence Project logo on one panel. The umbrella has a button that you can press to open it.

DNA Doe Project Original Dark Variant Long Sleeve T-Shirt – A minimalist long-sleeve tee featuring the DNA Doe Project’s iconic dark logo, designed to quietly show your support for identifying the unnamed and restoring lost identities through forensic genealogy.

The Cold Case Foundation Book – Follow the most riveting cases of an elite investigative team of volunteers brought together by a famed FBI Profiler dedicated to solving crimes no one else could

📖 If you enjoyed this story, you’ll love Eerie Escapes — the book that inspired it all. Learn more here.